Okay, I’m waiting for something and consequently finding it impossible to focus on my work in progress so instead I’m going to write… about writing. I think this is where I insert a gif of a snake eating itself and procrastinate for even longer via a deep dive into Giphy.

Since I was published, I’ve received a lot of interesting questions from readers, especially those working on books of their own. Something that comes up a lot is how I write, my process for turning this:

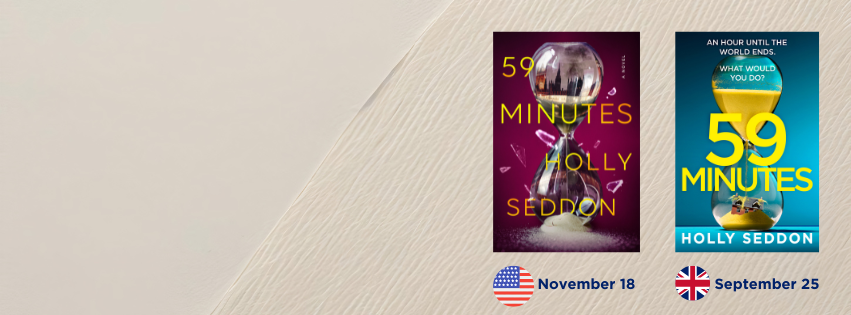

Into this:

So I thought I would attempt to boil it down and show you the raw ingredients.

1. The idea

So far, so obvious. But ideas come in all flavours and at all sorts of odd times. Sometimes they’re middle of the night bonkers (I once found a story idea I’d written on my phone that said something like ‘murder mystery but the twist is: a squirrel did it’). So all ideas are not created equal but there’s no harm in recording and exploring them.

I have a long, rambling note on my phone called ‘Stories to write’ and it’s a brain dump of exactly that. From one phrase ideas to fleshed out synopses. My second book, Don’t Close Your Eyes, out in July 2017 came from the one line on this note: “Good morning, Mr Magpie”.

2. Kick it around a bit

From the initial idea, I then take a few runs at it and try to flesh out a very, very rough story idea. Let’s go with the squirrel idea because it’s clearly Booker-worthy gold. From ‘murder mystery but the twist is: a squirrel did it’ I might ask questions like:

- Who is the victim?

- Where was he or she found?

- What were the injuries/cause of death?

- Is this a cold case or fresh inquiry?

- Who is investigating?

The more practical considerations like where the story takes place and the ages and physical characteristics of the characters tend to emerge when I start writing and are often a surprise to me.

3. Start writing

I’m what the NaNoWriMo website helpfully calls a “Planster” (I’ve even given myself that badge). In other words I like to have a loose plan and then wing it.

Once I’ve fleshed out that the victim in this instance is a vicar, newly arrived in a small village full of secrets and found dead in the woods behind his church by a poacher, I might decide that he was stabbed with a pointy tree root and found with injuries to his head. I’d maybe then think that the body was found last Sunday when he failed to arrive to prepare for a church service, and that the case will be investigated by a young police detective who grew up in the village. I decide that she escaped to join the police force in the city as an 18-year-old and that she found herself back here, reluctantly, for her first full detective role. Once I’ve worked those bits out, I get to writing.

I always launch in at the beginning but try to avoid preamble and scene setting, instead starting with action (the poacher firing his gun, his dog snuffling through the bed of crispy fallen leaves for a pheasant, finding instead the long, slim fingers of a very dead vicar) and let the scene set itself around the action.

As I write, I sew a few things in to help myself along. The vicar had some secrets, that’s for sure (because everyone does) and maybe this isn’t the first time the woods have borne witness to a grisly crime. Or maybe even a grizzly crime, if we’re doing this thing and going animal mad.

I tend to hurl myself at the first 10,000 words without thinking. This is the honeymoon period. Nothing will ever feel as good as these 10,000 words. I am in love with the premise, the characters and the location. The words flow. This work in progress is all I can think about, I’m like a teenager with a crush and then…

10,001.

I grind to a halt.

So this is when I…

4. Edit a little, plan a lot more

I go back through that first flush of writing, those 10,000 words I thought were so wonderful, and realise – with some relief – that they can be improved. A lot. And out of this edit, I get the next lot of ideas but I also see plot holes to sew up and assumptions to play with and I dream up extra characters and I note things to…

5. Research

I love research. I love research so much that it’s what I find myself drunkenly doing most weekend nights. Not for the work in progress, but just lazy Wikipedia thumb research on my phone about whatever actor happens to be on the TV screen at the time. But I love learning new things and I especially love reading first hand accounts of people living lives that are nothing like my own.

So for our bloodcurdling squirrel thriller, I would start to look at a few things:

- The day to day life, weekly tasks and job description of a country vicar.

- The living accommodation of said vicar.

- The training and recruitment process for new detectives (could our woman have been ‘sent’ to this village rather than applied, for example?).

- Who from a country police station would work on such a case with her?

- The kind of injuries that a squirrel could do to a human head, if it were to jump on it from a high tree.

- How hard someone would have to fall onto a thick, sharp root (and how sharp that root would need to be) in order to die from the injuries.

- How leaves could become extra slippery (through which type of rain or snow or sleet) in order to trip our vicar up and have him accidentally impale himself, while being attacked by this furry-tailed little f*cker.

All that remains then is to…

6. Write the thing

I know, this is a cheat, but there’s no two ways about it: This is when the slog starts. I’ve got another 70,000 or so words to write. So how do I fill it? One day at a time. A chunk of writing a day, whenever I can. Stopping when I’m dialling it in, when what I’ve written is forgettable the moment I get up to make another tea or pop to the loo.

And actually, although those 70,000 words stretch out in front of me like a terrifying and monotonous motorway, in reality, I’ve got a lot to cram in. And I’ve got a lot of cool places to visit along the way.

I need my detective to arrive on the scene, I need to learn her intentions (to solve the crime but what else? Her own ghosts to rest? Dealing with the family who wanted anything for her in life except a police career?). I need to help her discover all the possible reasons someone could want the vicar dead. But we also need to see the obstacles to her discovery and her intentions. I need her to make mistakes too, to be weakened by them but then come back stronger, fists flying. I need to see her solve the case. The book needs a satisfying ending.

7. Because the ending is never the ending

It’s the start of the editing. I try really hard to have a gap between writing my final scenes and then reading through. You’ve seen those irritating Facebook posts people share where every third letter in a word is missing but “89% of people read the whole word anyway” or whatever) well that’s what happens if you edit too soon. You see what you intended to write rather than what you did write.

I try to leave it as long as possible and then I start to go through from the beginning. I cut a lot, tweak words and move scenes around. I use Scrivener to write, and it’s a godsend for heavy edits. When I’ve finished the ‘sleeves rolled up mega-edit’, then I try to take another break.

When I’ve had enough of watching Netflix and Wikipedia-ing people, I come back to the work in progress but this time I’m in disguise. Now, I’m dressed as a reader. I want to see this novel how real readers will see it. I need to be the diner not the chef.

The way I cheat myself into feeling this way is quite simple. I send a copy to my Kindle app and I read it solely on my iPad. I highlight and annotate but I read it beginning to end like anyone else would. Then, when that’s done I park my iPad next to my computer and go through note by note making changes.

Then another read through on the computer, and then another read through on the iPad and eventually it’s ready to send off.

Of course, there’s a lot more to it than that, namely that my agent and editor will have a lot of notes (my agent will have been shown earlier drafts too). Notes like “Holly, are you alright? You’ve written a book about a squirrel killing a man of the cloth. Would you like a lie down? Shall I call someone?”) But essentially, in a massively long and rambling weirdly shaped nutshell, that’s how I write a book.